- Google Cloud

- Articles & Information

- Cloud Product Articles

- Basic Examples of Node.js

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

- Article History

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

First things first: you need to realize that Node is intended to be used for running standalone javascript programs. This isn’t a file referenced by a piece of HTML and running in a browser. It’s a file s itting on a file system, executed by the Node program, running as what amounts to a daemon, listening on a particular port.

Skipping hello world

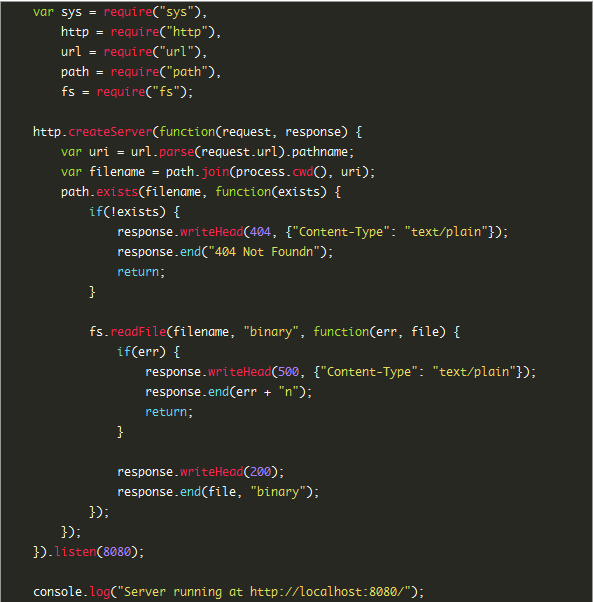

The classic example here is “Hello World,” detailed on the Node website. Almost everyone starts with Hello World, though, so check that out on your own, and skip straight to something a lot more interesting: a server that can send static files, not just a single line of text:

Thanks much to Mike Amundsen for the pointer to similar code. This particular example was posted by Devon Govett on the Nettuts+ training blog, although it’s been updated for the current version of Node in a number of places. Devon’s entire tutorial post is actually a great companion piece on getting up to speed on Node once you have a handle on the basics.

If you’re new to Node, type this code into a text file and save the file as NodeFileServer.js. Then head out to the Node website and download Node or check it out from the git repository. You’ll need to build the code from source; if you’re new to Unix, make, and configure, then check out the online build instructions for help.

Node runs JavaScript, but isn’t JavaScript

Don’t worry that you’ve put aside NodeFileServer.js for a moment; you’ll come back to it and more JavaScript shortly. For now, soak in the realization that you’ve just run through the classic Unix configuration and build process:

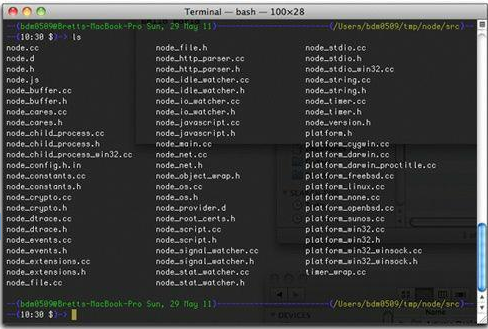

That should come with another realization: Node itself isn’t JavaScript. Node is a program for running JavaScript, but isn’t JavaScript itself. In fact, Node is a C program. Do a directory listing on the Node/src directory and you’ll see something like this:

For all of you who thinking that JavaScript is a poor language in which to be writing server-side tools, you’re half right. Yes, JavaScript is not equipped to deal with operating system-level sockets and network connectivity. But Node isn’t written in JavaScript; it’s written in C, a language perfectly capable of doing the grunt work and heavy lifting required for networking. JavaScript is perfectly capable of sending instructions to a C program that can be carried out in the dungeons of your OS. In fact, JavaScript is far more accessible than C to most programmers — something worth noting now, and that will come up again and again in the reasons for looking seriously at Node.

The primary usage of Node further reflects that while Node works with JavaScript, it isn’t itself JavaScript. You run it from the command line:

— (bdm0509@Bretts-MacBook-Pro Sun, 29 May 11) —————————— (/Users/bdm0509/tmp/Node/src) — — (09:09 $)-> export PATH=$HOME/local/Node/bin:$PATH — (bdm0509@Bretts-MacBook-Pro Sun, 29 May 11) —————————— (/Users/bdm0509/tmp/Node/src) — — (09:09 $)-> cd ~/examples — (bdm0509@Bretts-MacBook-Pro Sun, 29 May 11) — — — — — — — — — — —— (/Users/bdm0509/examples) — — (09:09 $)-> Node NodeFileServer.js Server running at https://127.0.0.1:1337/

And there you have it. While there’s a lot more to be said about that status line — and what’s really going on at port 1337 — the big news here is that Node is a program that you feed JavaScript. What Node then does with that JavaScript isn’t worth much ink; to some degree, just accept that what it does, it does. This frees you up to write JavaScript, not worry about learning C. Heck, a big appeal to Node is that you can actually write a server without worrying about C. That’s the point.

Interacting with a “Node server”

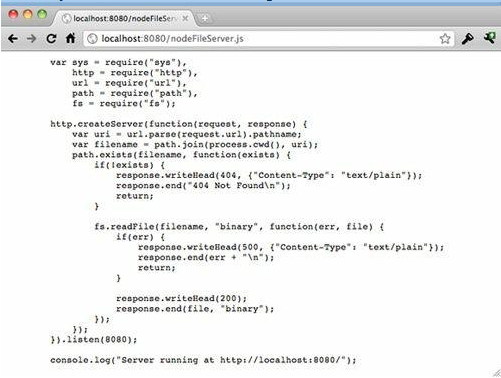

Make sure you still have your NodeFileServer.js code running via Node. Then you can hit your local machine — on port 1337 — and see this unremarkable output.

Yes, this is about as mundane as you can get. Well, that is, until you realize that you’ve actually written a file server in about 20 lines of code. The output you see — the actual code of the script you wrote — isn’t canned in the script itself. It’s being served from the file system. Throw an image into the same directory, and simply add the name of the image to the end of your URL, like https://localhost:8080/my_image.png:

Node happily serves this binary image up. That’s pretty remarkable, when you again refer to the brevity of the code. On top of that, how hard would it be if you wanted to write your own server code in JavaScript? Not only that, but suppose you wanted to write that code to handle multiple requests? (That’s a hint; open up four, five, or 10 browsers and hit the server.) The beauty of Node is that you can write entirely simple and mundane JavaScript to get these results.

A quick line-by-line primer

A NodeJS module helps you read large text files, line by line, without buffering the files into memory.

Installation:

npm install line-by-line

There’s a lot more to talk about around Node than in the actual code that runs a server. Still, it’s worth taking a blisteringly fast cruise through NodeFileServer.js before moving on. Take another look at the code:

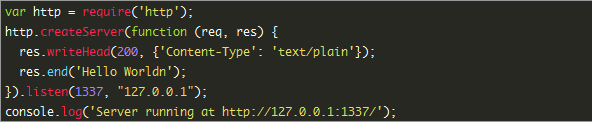

First, you have a call to a function called require(). The use of require() has been a long-standing request by programmers. You can actually find this mentioned in some of the discussions on JavaScript modularity, as well as germane to CommonJS, and a pretty cool implementation by O’Reilly author David Flanagan from 2009. In other words, require() may be new to you, but it isn’t an untested, careless piece of Node code. It’s core to using modular JavaScript, and something of which Node takes heavy advantage.

Then, the resulting http variable is used to create a server. That server is handed a function block to run when it’s contacted. This particular function ignores the request completely and just writes out a response, in text/plain, saying simply “Hello Worldn”. Pretty straightforward stuff. In fact, this lays out the standard pattern for Node usage:

1. Define the type of interaction and get a variable for working with that interaction (via require()).

2. Create a new server (via createServer()).

3. Hand that server a function for handling requests. The request handling function should include a request …… and a response.

4. Tell the server to start handling requests on a specific port and IP (via listen).

Twitter

Twitter